An overwrought, poorly written, and apparently unedited opinion piece by Jay Lehr and Richard T. McGuire tearfully contrasts America's Golden Age of resource exploitation with our current era of business-thwarting "junk science":

In the past we used our natural resources freely. We took great pride in our ability to convert resources into products with a direct benefit to the public. We turned trees into houses, coal and iron into automobiles.

Today we hear that we must stop using our economic resources. Scale back. Harvest fewer trees. Drill fewer oil wells. Use less fertilizer. Build no new power plants.

Oh, the humanity! Needless to say, Lehr and McGuire immediately launch into a rant on environmental hysteria, and the privations we've all suffered as the result of imaginary terrors like the "asbestos scare." Intellectual seed is spilled - or perhaps I should say "dribbled" - over the cornucopian fantasy of "wise use." And of course, the mythical

Alar Scare - that spavined old warhorse of the anti-environmental ultra-right - is dutifully trotted out as evidence of public irrationality.

Though they try gamely to come across as moderates, the authors simply can't keep their inner demons at bay. One moment they're cautioning us against irrational fears; the next, they're flailing around like Linda Blair in

The Exorcist, screeching about the

[T]echnically unsupportable global warming assumptions being pressed upon us by a scientific community receiving $4 billion a year to prove the unprovable, the United Nations wishing to expand its power, big business desiring to drive small business out of business, foreign nations desiring to shackle our economy, environmental zealots wishing to undermine our capitalistic economy and a will [sic] co-conspiring news media which thrives on all manufactured crisis.

As you can see, Lehr and McGuire find it very difficult to keep their paws out of the cookie jar of Conservative Cliché. They're aware that they might scare ordinary people away with this deliriously paranoid babbling, though, so they quickly strike a rather pathetic defensive pose:

We are not against wetlands or in favor of dust and noise. We believe in the regulation or [sic] our natural resources. We don't think anyone has the right to spray poison anywhere he likes and we acknowledge the need for community involvement.

In other words, it's not that the environment

shouldn't be protected (here and there, now and then). It's just that, like Dick Cheney, we've got "other priorities":

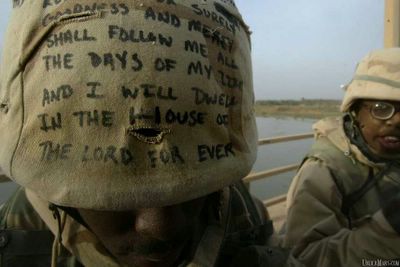

Aside from the obvious and unfortunate cost of our war in Iraq, we all agree that our educational system is in need of major overhaul. We are far from winning the war on drugs. In many states our roads and bridges need repair. And in too many places our water and sewerage systems need improvement to protect our own drinking water.

Isn't this too cute for words? The "unfortunate cost" of the Iraq War is a reason why we can't afford to protect the environment. Sounds like another good reason not to have started it!

Lehr describes himself elsewhere as a libertarian committed to market solutions, so it's very possible that all his tender concern for public infrastructure is a mere

ignis fatuus. In any case, it's interesting that he thinks people will be impressed by the argument that we should worry less about protecting the environment, and more about protecting our drinking water.

Towards the end of the piece, Lehr and McGuire ask the really

hard questions: questions so incoherent and dishonest that to accept them as rational on any level is to forfeit one's status as a sentient being:

Saving the world from Radon, Asbestos, arsenic, ozone and CO2 is great for raising money, but what is the real cost to the nation's industry?

What's the cost to industry of "saving the world"? Hmmm...let me do the math, and get back to you.

Wetlands, wilderness and unobstructed views are vital to us all, but where, how much and at what cost?

That's a good question, and we'd better err on the side of caution 'til we figure it out. As far as wetlands are concerned, the nation's lost about fifty percent of them. That doesn't sound too bad - perhaps - until you note that states like California and Louisiana and Florida have lost up to

90 percent of

their wetlands. Personally, I don't see any reason to shoot for 95 percent.

By the way, Lehr is the "science director" of the

Heartland Institute, a Scaife-funded anti-environmental group whose board of directors includes plenty of folks from the fossil-fuel, automotive, financial, and tobacco industries. Of course, the site that printed these ravings didn't see fit to give its readers any background on Lehr or his cronies.

Since I'm a blogger, I may as well get the most out of my irredeemable lack of standards and decency: These people are vermin.