Robert M. Jeffers quotes Derrida: "My death; is it possible?" He goes on to discuss certain manifestations of the denial of death, and makes this eloquent point:

It is a function of money, and of the illusion that money and power can be used to work our will irrevocably on the world.Meanwhile, Cervantes discusses "secular apocalyptics," and makes this eloquent point:

One starts to suspect that, at least in the case of many people, these are expressions not of fears, but of wishes. Certainly that is true in the case of the Christian millenialists, but is the psychology of the secular apocalyptics similar? Do they yearn for a better world on the other side of the Great Dying?My argument would be that for the most part, the psychology is not merely similar, but virtually identical, and that this equivalence between secular and religious psychology is more the rule than the exception. (I suppose one could argue over which viewpoint involves a greater betrayal of reason. But that would mean assuming that reason per se is something that ought not to be betrayed, which is a superstition I try my best to avoid.)

Walter Benjamin, as he watched the rise of the political movement that would eventually drive him to suicide, said of contemporary society:

Its self-alienation has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure.But of course, this "supreme aesthetic pleasure" presupposes a self that lives through it. Which suggests that the motive force here is not self-alienation so much as world-alienation.

Then again, is there necessarily a difference? In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Adorno and Horkheimer write:

The compulsively projecting self can project nothing except its own unhappiness....For the ego, sinking into the meaningless abyss of itself, objects become allegories of ruin, which harbor the meaning of its own downfall.A somewhat quaint formulation, I'm afraid. And yet it's hard to avoid the suspicion that the world is less the cause of our misery, than a convenient scapegoat for it. If so, it's no wonder some people gloat over the idea of its doom. It's the ultimate form of what AA calls "pulling a geographic"...the notion that everything will be fine if you just go somewhere else.

On the other hand, if you've given up on utopia, you can always glamorize dystopia. Don't chemical ponds have a certain beauty, after all, when seen from a God's-eye view?

Apocalypse appeals to human beings in a way that - to take the most charitable view - is inexpressible enough to make most people who speak of it seem...well, kind of vapid. On the secular side, the problem may be that apocalyptic thinking often exalts the self while pretending to cast it away in favor of "objectivity." Or maybe it's because striking a pose of aestheticized equanimity towards one's own death is so much easier if, as Tom Lehrer sang, "We will all go together when we go." That way, at least, the emotional discomfort of being survived doesn't arise. When it comes to extinction, apparently, there's strength in numbers.

Things are no better on the theological side, of course. The religious incoherence (and materialist vulgarity) of the Jew-annihilating Darbyist apocalypse goes beyond vapidity, and proceeds directly to evil.

At any rate, when contemplating the end-times through the eyes of secular or religious eschatophiles, I'm struck less by awe or humility than by the eerily similar forms that human vanity and human misery take on both sides of this supposedly profound philosophical divide, as they seek to "work their will irrevocably upon the world."

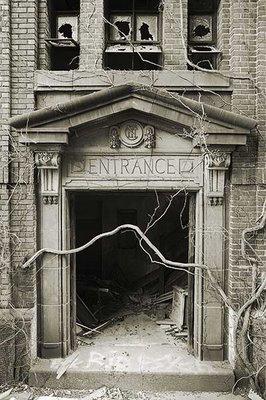

(The photo above is from Sean O'Boyle's Modern Ruins).

1 comment:

Speechless,

You're talking about a different type of self-annihilation, though, because you're basically coming from the Christian mystical tradition (please correct me if I'm wrong, by all means).

I can't relate that so much to Christian fundamentalism, which I really do think is materialist at its core, both in terms of its creepy idea of what constitutes redemption and its obsessive vanity. I certainly don't mean "materialist" in the healthy sense of recognizing one's subjection to what Simone Weil called "gravity"; I mean it in the sense of mere acquisitiveness and self-aggrandizement.

I do think that secular apocalyptics are closer, wittingly or otherwise, to the tradition you're espousing...if for no other reason than that they're a bit further along the path of rejecting false comforts, which seems to me to be a prerequisite for finding real ones.

Since this rough sketch of a post draws heavily on the Frankfurt School - which I think represents one of the 20th c's more interesting attempts to come to grips with religion - I should mention Siegfried Kracauer's essay "Those Who Wait," which makes a couple of points similar to yours. He identifies what he calls "short-circuit people," whose religion involves "plucking a fruit which has not ripened for them and which they themselves have not ripened towards," and who end up trying fanatically to shout everyone else down, in order to prove their faith to themselves. On the other hand, he sees certain types of skeptics as the real practitioners of "spiritual" renunciation...renouncing even salvation itself, and thus having the potential to do good without any thought of reward in the afterlife (I think I'm probably extrapolating beyond Kracauer a bit here).

There's a lot to be said for realizing that if any good is to be done in the world, you're going to have to do it yourself.

So perhaps the real problem with apocalyptic thinking - right and left, secular and religious - is that it's an abdication of responsibility...people would rather give up the world than accept responsibility for it. If that makes sense. Anyway, I believe that was what I was trying to get at here.

Post a Comment