Robert M. Jeffers objects to what he calls the Hegelian tendencies of George W. Bush:

Forces are in play in his imagined Middle East; not people, not men and women with histories and cultures and governments, people with families and desires and appetites and needs. Simply "forces." The world is much easier to understand when you reduce it to simple, empty concepts which can mean whatever you want them to mean.RMJ contrasts this with the attention of Jesus to the individual; where Bush sees “forces,” God’s eye is on the sparrow.

I'm reminded of the epilogue from David Stacton’s odd and remarkable novel The Judges of the Secret Court (1960), which deals with the lives of Edwin and John Wilkes Booth:

It was Julia Ward Howe who once asked Charles Sumner if he had heard of young Booth yet.Still, it seems to me that Bush's "simple, empty concepts" are well within the mainstream of what we ordinarily call religion. The forces of Good and Evil are at war, we’re told, and if innocent individuals “with families and desires and appetites and needs” fall victim to the friendly fire of the righteous, so be it. Death is only a dream, and God will know His own.

“Why no, Madam,” said Sumner. “I long since ceased to take any interest in individuals.”

“You have made great progress, sir,” Julia told him. “God has not yet gone so far – at least according to the last accounts.”

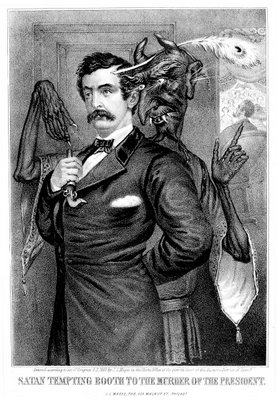

This is a problem with human beings per se. We tend to see great economic, political, biological, or spiritual forces at work everywhere, and people as their expendable puppets. In the cartoon above, Satan tempts John Wilkes Booth to kill Abraham Lincoln. Apparently, the artist felt that Booth couldn't have devised a specious, self-aggrandizing justification for murder without supernatural help.

RMJ goes on to make an important point:

The language of rights is a slippery one. It sounds like an absolute, something that must get acknowledged and can never be removed or taken away. Yet even the right to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" can be taken from you by the State of Texas; Governor Bush sometimes made quite sure of that.This frightening ability to grant and revoke rights is at the center of Simone Weil’s elevation of obligations over rights (which can be summed up by paraphrasing Philip K. Dick: Obligation is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away).

This begs the question of what one feels one’s obligations to be, which is an interesting – and not at all pleasant - thing to ponder while sitting in the United States and looking at pictures like these. What’s more important: The right of these people not to be killed? Or our obligation not to allow them to be killed?

Considering where the path of obligation may lead, it’s no wonder that we generally prefer the language of rights. It lets us appeal to the consciences of others, instead of our own. It lets us tell tyrants to stop themselves (from a comparatively safe distance, in most cases), instead of obliging us to do whatever’s necessary to stop them.

But what is necessary? A Jewish tradition says that the Messiah will make “a small adjustment” to the world in order to redeem it. Most assassins have held to a crude secular form of that idea. Exterminate a politician or two, the logic goes, and a bright new day will dawn for everyone (except their victims, and their supporters, and anyone who doubts the value of retaliatory or preventative killing).

None of it works, of course. Like the delusion of capital punishment, the idea that you can effectively punish murderers is based on a tendency to ignore the consequences of violence in favor of something called “closure” (which doesn’t actually exist outside of bad art, but is increasingly becoming a synonym for “justice”). To quote Stacton once more:

It is the rest of us who have to go on living with what they did, with what life has done, with what the world does, with what has been done to us.

3 comments:

Exterminate a politician or two, the logic goes, and a bright new day will dawn for everyone

this also seems to be the thinking of the cuban exile community in miami right now - apparently the death of castro will suddenly transform cuba into a capitialist paradise that will welcome them home with open arms.

This is a problem with human beings per se. We tend to see great economic, political, biological, or spiritual forces at work everywhere, and people as their expendable puppets.

ntodd blogged about this a few days ago, suggesting:

The raw statistics are numbing, though. Perhaps it's more instructive to look at specific instances like the Canadian family killed by Israel, or Ali being orphaned and losing his arms thanks to the US. Now think about that kind of horror unleashed on you and your loved ones. Tends to humanize the conflict better than any numbers scrolling by on a newsticker, doesn't it?

The deaths of leaders of personality cults often do have great effect; look at what happened to China after the demise of Mao, for example.

look at what happened to China after the demise of Mao, for example.

I guess. If he'd been assassinated, though...

Eh, beats me. I'm really just thinking out loud in this post. I don't think there's any good solution for these problems.

Post a Comment